History

Christian worship has been offered on or near this site since about 650 AD when a minster was built during the reign of Eanswythe’s brother Earconberht (not, as previously thought, by her father Eadbald). It is believed to have been the first religious house with an abbess in the country, but since the historical record is very sparse and was written centuries after Eanswythe’s lifetime there is little that can be known with any degree of certainty.

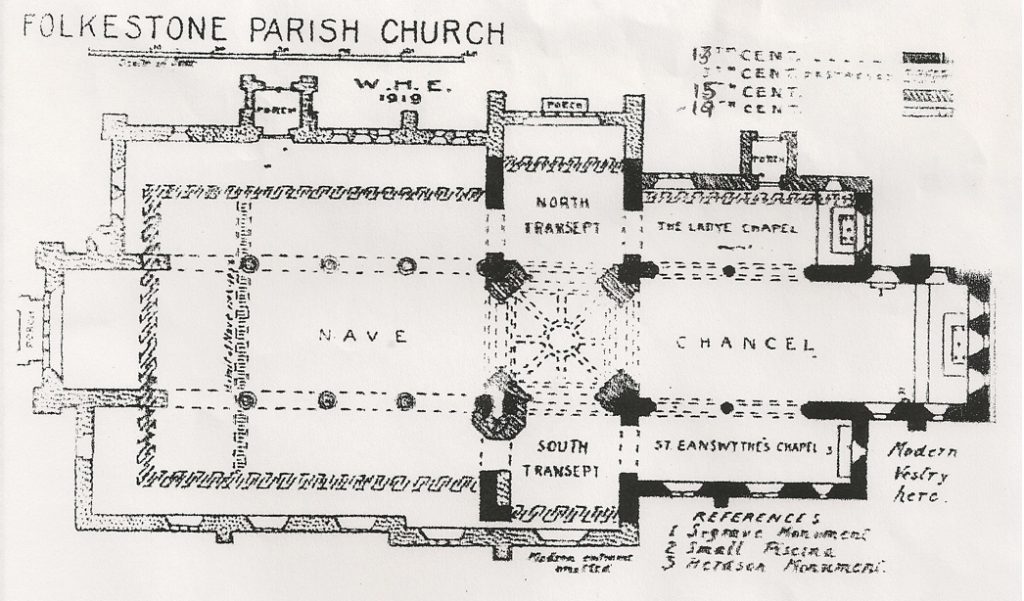

Recent research points to Eanswythe’s birth being in about 630 AD: the remains held in the church are of a young woman who probably died between the age of 17 and 21 so the dates are consistent with her being the first abbess as related by the stories about her life. Her relics became a focus of pilgrimage and in 1138 were brought into the chancel of the present church (the fourth to occupy this site) on 12 September – the date we still keep as our Patronal Festival.

The various Eanswythe legends are discussed here on the Finding Eanswythe site.

In the 11th century the Priory was established but was suppressed, like almost all the others, by Henry VIII in 1534 and the church entered a long period of neglect and decline.

Canon Matthew Woodward, the vicar from 1851 to 1898, transformed it into the beautiful church you see today, with stained glass, murals and mosaics of the highest quality.

Folkestone Priory

W. H. Elgar (1919)

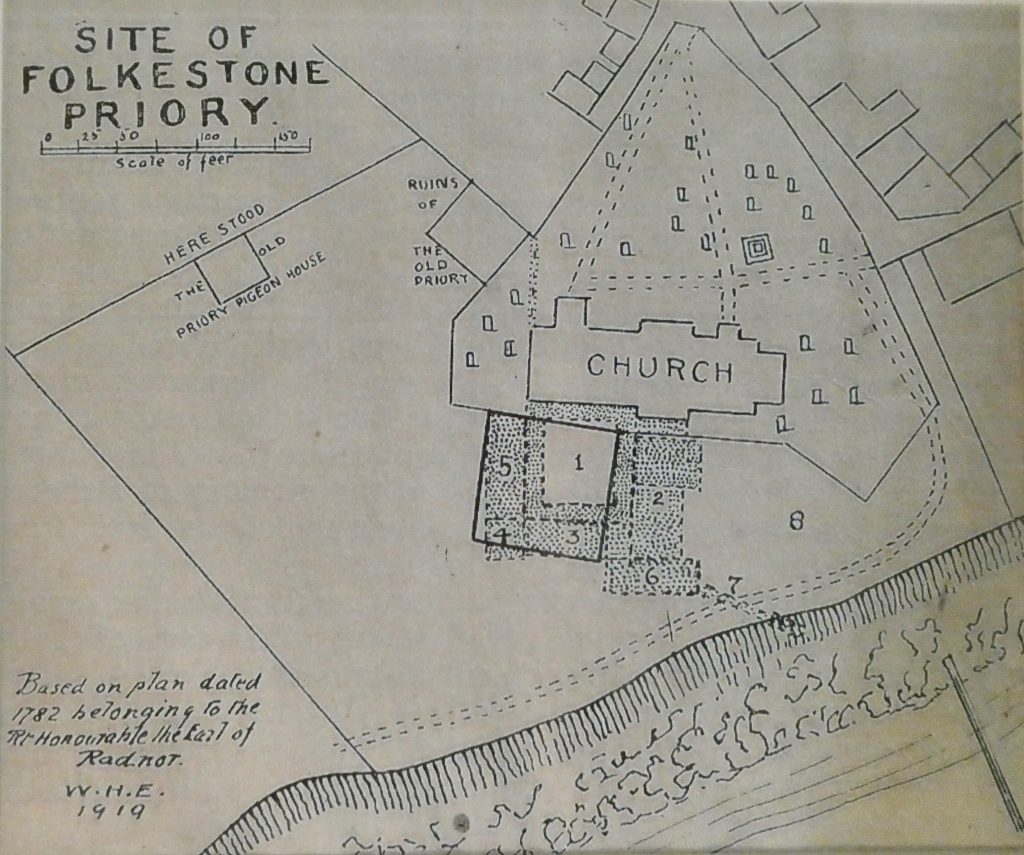

Although, with the exception of the church, almost the whole of this institution has disappeared, it may not be out of place to here set down what is known of it, as far as the writer is able; especially as it is most unlikely that excavations will be undertaken to expose any existing foundations for many years to come, for much of the site is occupied by the buildings known as Priory Gardens and a portion of the Vicarage.

St. Eanswythe’s nunnery stood near where the old Bayle Fort now is, and on this site was rebuilt a monastery in 1095. The monks subsequently asked to be removed out of the castle precincts; the present church was commenced in 1135. The two sites should not be confounded.

It is just possible that some particulars as to the first nunnery may be deduced from a study of the old maps and plans in the possession of the Right Honourable the Earl of Radnor, to whom the writer is indebted for the plan upon which the present observations are based. This plan is part of a survey made in 1782.

A glance at this plan will show that the paths through the churchyard are as they were, with the exception of one to the east of the church, which now passes outside the wall. The churchyard then had not been extended to its present size, a piece, stretching westwards to about where the priory pigeon house stood, has been added. It will be noticed that a square is drawn with a continuous line containing the tinted portions marked 1, 3, 4, and 5, This square occurs on the 1782 plan, and in it are these words, ‘Here stood the ruins of the old mansion house.’ It is this marked area and the two others to the northwest of it that give the clue to the plan of the priory. It will be just as well here to quote from Hasted’s History of Kent:

“The new priory was accordingly built upon the spot or plot of ground granted for this purpose by Sir William de Abrincis as above mentioned, close to the south side of the new church, with which, as appears by some doorways still to be seen in the wall of it, though long since filled up, the priory communicated and which thenceforward became the conventual church to it, both church and priory being dedicated to S.S. Mary and Eanswyth.”

We now pass to the time of the dissolution in 1535, and, still quoting from Hasted, “As soon as the King’s Commissioners had turned out the monks and taken possession of the priory, such part of the buildings the materials of which could produce any profit were ordered for the lucre of them to be taken down and sold.”

Two years after, “the house and site of it, with all houses the house and site of it with all homes, buildings, orchards, lands, and gardens within the precincts,” were granted to Edward Lord Clinton. Within a few years of this event Folkestone was visited by Leland, and in his ‘Itinerary’ he says:

“The Toune shore be al lykelihod is marvelously sore wasted with the violens of the se; yn so much that there they say that one Paroche Chyrch of our Lady and another of St. Paule ys clene destroyed and etin by the se. Hard upon the shore yn a place cawled the Castle Yarde the which on the one side ys dyked and theryn be greate ruines of a solemne old nunnery the walles whereof yn divers places apere great and long British Brikes and on the right hand of the Quier a grave Trunee of squared stone. The Castel Yarde hath bene a place of great burial; yn so much as when the se hath woren on the Banke bones appere half stykyn out. The paroche chyrch ys therby made also of sum newer worke of an abbay. Ther is St. Eanswide buried and a late therby was the visage of a priory.”

Quite a graphic description of the state of the old castle and the ruins of the nunnery and a clear reference to the priory by the Parish Church.

Hasted gives a description of what he saw about 1800: “All that remains of it and indeed has for a great number of years past, is a small part of the foundation, and an arch in the wall of it, about three feet above the ground, which is turned with Roman or British bricks of which there are several among the mixed foundations and under that one more modern of newer stone, seemingly for a doorway. From these ruins which are near the south-west corner of the church, where there is much uneven ground from the rubbish lying about it, there goes a large sewer of stone masonry, which runs underground slanting south eastwards, large enough for a man easily to creep through, the end of which appears, sticking out of the edge of the broken cliff over the shore”, probably the same as Leland noticed.

Between the times of these two observers a mansion had stood upon the site of the priory. A very small sketch of this is to be seen on an old map at the Manor Office. Most likely a part of the priory was incorporated in the mansion. It should be noted that our plan of 1782 was made before Hasted published his ‘History of Kent.’

Probably some building stood near the spot marked with figure eight for the accommodation of the infirm, and it is possible that the prior himself had a separate house, which might have formed part of the house near the east gate of churchyard, and now the residence of Mrs. Sturt.

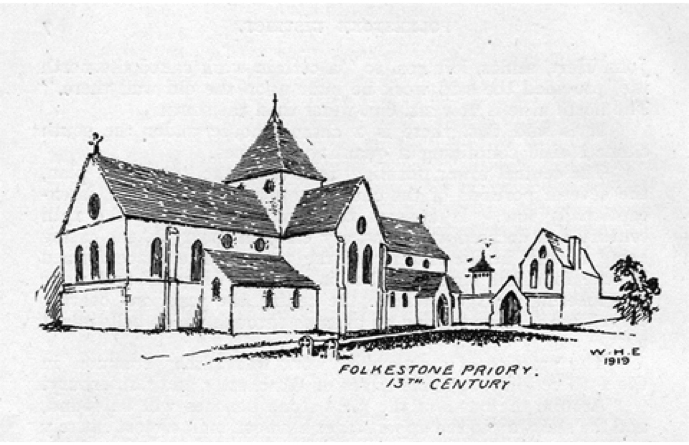

The view accompanying the plan (below) is an attempt to show what the priory looked like in the 13th century to an observer north-east of the church. From this point the cloister and its adjacent buildings would not be visible, but both the other structures marked on the old plan could be seen.

The larger of these was most likely the guesthouse, for this was its usual position, and the pigeon house appears above the wall, which has been assumed connecting the west-end of the church with the guesthouse. In this wall the principal gate has been placed.

From what has been said of the history of the church in the previous article the changes in its appearance are all accounted for.

Mr. H. O. Jones, the Deputy Borough Engineer, has kindly supplied particulars, which enabled the sites of the priory house and the guesthouse to be plainly described. The pigeon house stood just in the shrubbery of West Cliff Gardens, close to the present churchyard wall; and the guesthouse occupied about half the space (the eastern half) to the right of the path leading from the church to West Cliff Gardens.

The Church in the 21st Century: New Pilgrimage Routes

Our church is now part of two modern pilgrimage routes, both of which commemorate the royal women who were prominent in the earliest days of Christianity in Kent. The Royal Saxon Way connects Minster Abbey and our church in Folkestone, while the Royal Kentish Camino connects our church with St Mary and St Ethelburga, Lyminge (also on the Royal Saxon Way) and with St Martin, Canterbury, which was founded by Bertha, Eanswythe’s grandmother.